Washington County Durham

HOME WHAT'S WHERE GO TO NEXT PAGE (2/2) MINING COLLECTION 1

Memories of Mining

Usworth Colliery Disaster - 1885 (1/2)

- Page 1

- Page 2

- Page 3

- Page 4

- Page 5

- Page 6

- Page 7

- Page 8

- Page 9

- Page 10

- Page 11 - Colliery Map

- Addendum

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Usworth Colliery, many years after The 1885 Disaster. Note Railway Terrace & Usworth Green Prefabs.

• • ◊ • •

Articles from Durham Chronicle

( First Report: Friday, 6th March 1885 )

USWORTH COLLIERY PIT DISASTER

FORTY TWO LIVES LOST

Death of two of the rescuers

Another of those mining disasters, which from time to time have happened in this county, occurred at Usworth Colliery late on Monday night, resulting in the loss of 41 lives. The county of Durham has been the scene of a succession of these calamities since the dreadful explosion at Seaham Colliery on September 8, 1880, which, it will be remembered, was followed by the explosions at Trimdon, Tudhoe, Stanley and now at Usworth Colliery. The scene of the present disaster is situated on rising ground, about equidistant from Newcastle and Sunderland and about a mile and a half distant from Usworth Station. The colliery was first sunk about 40 years ago and the proprietors were then Mr J Johnasson of Newcastle and Sunderland and Sir George Elliot MP. About three years ago the colliery was transferred from the then proprietors to the present owners, John Bowes Esq and Partners who are also the proprietors of Wardley Colliery and one of the most extensive colliery owners in the North of England. Mr Alfred Palmer, brother to Mr CM Palmer, MP is manager at the mine. Mr Palmer’s assistant in the underground management of the colliery was Mr John Robinson who was succeeded about twelve months ago by Mr Lindsay, who in his efforts at this explosion, in the work of attempting to rescue the entombed miners all but lost his life. The pit has two shafts, the Wellington East and the Wellington West and these are divided by a bratticing. This is called the main shaft, and by it the colliery is principally worked, although in addition there is the back shaft, by which the men uninjured in the East Pit were brought to bank, and which is mainly used as a downcast shaft. The three seams of coal worked are the Maudlin, which is separated by 10 fathoms from the Low Main (where the explosion occurred) and the deepest of the three is the Hutton, which is 180 fathoms from the surface. Usworth Pit is one of the deepest in the county. The mine is ventilated by means of a large Guibal fan blast, 45 feet in diameter. From the commencement of the colliery the coal won has been found to be of a very fiery nature, and the utmost precaution has always been exercised to prevent any disaster. The coal won is chiefly that of the best steam and gas kinds, and during the late ownership of Messrs Johnasson and Sir George Elliot vast quantities were sent by rail direct to the gasworks of the London Gas Company. Up to about a month ago the colliery worked pretty regularly and averaged from ten to eleven days per fortnight. Since then the men have only averaged about six days per fortnight. About 600 men and boys are employed at the colliery. The output of coal averages about 1,000 tons per day.

The facts leading up to the explosion are very brief. The colliery is worked on the two shifts system. The back shift men came out of the mine about 5 o’clock on Monday night and the night shift men were due to go into the pit at nine o’clock. In the interval, what is known locally as the four o’clock shift go down, to prepare the workings for the night shift men; thus at the time of the accident there were fewer men in the mine than at any other period in the day, but there is no doubt that had the explosion occurred half an hour later the loss of life would inevitably have been increased to over 100 men and boys, as at the very moment the disaster occurred the night-shift men were gathered on the ‘heap’ ready to descend and had been ‘called.’ The first batch of the night-shift men were actually stepping into the cage when a loud report was heard and a cloud of dust rushed up the east shaft, indicating, as those at the bank only too well knew, that another disastrous explosion had been added to the record of sad catastrophes in the mining industry of the North of England. It only took a moment to realise the fact, and then the intelligence was spread far and wide, and not withstanding the late hour of the night, there was soon a large gathering of anxious and sorrowing people at the pit mouth.

Page 1

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

Pit Terms

The Heap (Heapstead) - where men get into and out of The Cage at Bank.

Bank - the surface of the mine.

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

At the time it could scarcely be ascertained what was the exact number of men in the mine, but it has since been found that there were between 30 and 35 in the East Pit and about 45 in the West Pit, where it soon became known that an explosion had occurred. The officials of the colliery, Mr Alfred Palmer, Mr Lindsay, Mr Morland and others were soon informed of the accident and were quickly present. A hasty survey of the surroundings showed that the west shaft was blocked to such an extent that very little hope was even then entertained that the entombed miners could be reached in time to save their lives. Exploring parties were at once organised and it was soon discovered that great damage had been done to the workings and that considerable difficulties would have to be encountered before the unfortunate men in the mine could be reached. Meanwhile the sad news spread through the village and the neighbouring village of Washington and the roads to the pit mouth were speedily thronged with colliers and their families, many of whom knew too well that a sad bereavement would be their lot.

Amongst others who arrived as soon as possible were Drs Wilson, Gardner and Jackson; Mr Willis, Government Inspector for Northumberland; Messrs Forman and Patterson of the Durham County Miners’ Association; Mr Alex Blyth, Mr Steel and Mr Parkinson of the Northumberland and Durham Miners’ Permanent Relief Fund; a number of viewers who had heard of the explosion, and other persons, all anxious to render what service they could to rescue the entombed men. At intervals, the men in the East Pit who were injured were all safely got to bank, and the efforts of the exploring party were directed to clearing the falls and securing good ventilation. Unhappily, at the very outset of their explorations, two of the first exploring party met their death in their heroic endeavour to succour the entombed. Their names are Elijah Donnelly, back overman, who leaves a widow and four children; and Richard Coldwell, or Slee, master shunter, who leaves a widow and two children. The story, as told by Mr Lindsay, who was extremely exhausted when brought to bank, was very touching. He, along with the two deceased, in penetrating the workings, were over-taken by the fatal after-damp. These two pioneers of the exploring party, on being overcome by the noxious fumes, endeavoured to return, but their strength failing them, they were both literally dragged by Mr Lindsay for a distance of fully 40 yards, when his own strength gave way, and he was compelled to leave the men to their fate, but not before he had bravely imperilled his own life; for on reaching the bank he was in an almost unconscious state, and had to be supplied with restoratives. This sad incident intensified the sorrowful feelings of those at the pit mouth, for it was but an hour ago that the two rescuers chivalrously stepped into the deep, dark and dangerous mine to the rescue of their fellow men. Mr Patterson, of the Durham Miners’ Association, descended the mine at 5 o’clock on Tuesday morning and remained there during the greater portion of the day, notwithstanding that he is still suffering from the effects of the unwholesome vapours inhaled whilst exploring at the Seaham Colliery explosion. Throughout the day Mr Palmer and other officials were indefatigable in their exertions to bring about a speedy rescue of the entombed miners, whether dead or alive. Relays of explorers were kept in readiness to render any assistance required, but the whole day was mainly spent in clearing the ways and putting in bratticings and stoppings. The west shaft was so much blocked that the work of clearing it could only be effected by means of the workmen descending in the ‘kibble’, it being impossible to work the cage. As the direful news spread, miners from all parts of the county made their way to the scene of the disaster and every train set down at Usworth Station a large number of passengers, until the number assembled in the vicinity of the pit must have numbered many thousands. There were no emotional scenes amongst the crowd. They gazed sadly but silently on the work as it proceeded and bravely awaited the worst. As soon as the extent of the disaster was known, the colliery carpenters set to work to make the coffins, and the melancholy ‘rat-tat’ was heard all day long. The fitters’ shop was set apart as the dead-house, and there the bodies will be conveyed when brought to bank for the purpose of identification and coffining. At the colliery offices there was a full supply of splinters, leg guards and restoratives ready for use in the event of any of the men being brought to bank alive. Mr Alexander Blyth, secretary of the Northumberland and Durham Miners’ Permanent Relief Fund; Mr William Steele, agent; and Mr Parkinson were early at work preparing a list of the dead and making ready to distribute the amount of funds to which the bereaved families are entitled. From their list the number of killed was brought up to 38, including the two explorers. All the men killed were members of the fund and therefore entitled to its benefits.

Page 2

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

Pit Terms

Afterdamp - a highly dangerous mixture of gases resulting from an explosion or fire.

Ways - short for Roadways i.e. tunnels.

Brattice - a tarpauline-like sheet used to direct air flow. Permanent bratticing was made from wooden planks / boards.

Stopping - a structure constructed to stop air flow from one roadway to another.

Kibble - a large steel 'bucket' used, in place of a pit cage, to carry men and materials.

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

Coming to the cause of the accident, nothing has been definitely ascertained as yet, but the seat of the explosion is believed by practical and experienced men at the colliery to be about 100 yards from the shaft bottom, where there is an engine which works the coals out of the Maudlin seam. It is supposed that here there was an accumulation of gas, which reached the boilers, and thus caused the explosion. It should also be mentioned that a new scaffold was in course of construction on the night of the explosion. The scaffold was some distance from the workings but it is not known whether the work being carried on there was in any way contributory to the cause of the explosion. With one single exception the working of the colliery since it was first sunk has been marked by an immunity from accidents of a disastrous character. There have been two previous explosions, one of a serious and the other of a comparatively minor character. About thirty years ago, when candles were used in the mine, an explosion occurred which resulted in the loss of seventeen lives and through a similar accident two lives were lost a few years ago.

The horror of this catastrophe was well-calculated for a moment to paralyse the efforts of those above ground and in safety and therefore able to render assistance to the unfortunate men below; but this feeling was only momentary and soon the neighbourhood of the colliery was a scene of busy, anxious activity. To take steps to ascertain the extent of the accident and what means were necessary to alleviate its effects, as far as possible, was of immediate importance, and neither officials or men were slow to recognise this fact. In a very short period of time Mr Morland, the manager, and Mr Lindsay, the underground manager of the colliery, arrived, and they were speedily followed by Mr Alfred Palmer, the managing viewer. A very brief examination made it apparent that the main shaft was, for the time being, useless, being blocked up with falling debris. Attention was therefore turned to the back shaft, which is situated only about 40 feet off, and which is used for ventilating purposes; and by it they were able to descend to the seam in which the explosion had taken place. About a dozen gallant volunteers, under the direction of Messrs Morland and Lindsay, descended by means of a kibble and chains and, guided by the indications of the course of the explosion, they discovered several men and boys, one of whom, a waggonman named Ridley Taylor, was just barely alive at the time. They were found but a short distance away and were as quickly as possible brought to the bottom of the shaft and by means of the kibble brought to the surface, where Dr Wilson, Birtley; Mr Jacques, Washington; Dr Jackson, High Usworth; Dr Gardener, Old Washington, were in attendance to render the such assistance as lay in their power. Amongst the first to reach the surface was a lad named Thomas Dobson, a fireman, who was scalded about one leg. A man named Buckham succeeded him. He was suffering from scalding and burns and wounds to scalp and shoulder. Prest, a Stoneman, who came next was suffering from bruises of the muscles of the back. These three, though painfully injured, have fortunately every prospect of more or less complete recovery. When William Howarth, fireman of the South Maudlin engine, emerged from the pit mouth he was in a state of collapse. Stimulants were applied, with the effect of producing partial reaction. It was hoped that this reaction might be maintained and become permanent, but unhappily that hope was not realised. He had seemed to have received injuries to the head, shoulder and side and after some hours of extreme agony he succumbed to his injuries. The next man sent up was the waggonway man, Ridley Taylor, who was in such a prostrate condition that he expired almost immediately on coming to view above ground. He appeared to have suffered a fracture of the right ankle and might possibly have other wounds, but he was not uncovered, as he was clearly dead before he came within the scope of medical aid. The fact that some of these unfortunate men were suffering from scalds not unnaturally give rise to the idea that the catastrophe might have been the result of a boiler explosion and this conjecture seemed to be further warranted by the fact that within about one hundred yards of the low main seam there is, or was, an engine and two boilers to work the coals out of the Maudlin seam. This theory still finds supporters, though unfortunately a hope which in the first instance gave rise to, scarcely any longer exists, that the other men in the West Pit might be out of danger.

Page 3

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

The men in the East Pit had heard such a noise as might have been occasioned by extensive subsidence of coal, but were by no means aware of the extent of the misfortune which had befallen their comrades in the West, or how far, if at all, it might affect themselves. They felt no stoppage in the passage of air, but experienced a smell, as one of them said, like burning tar, and were sufficiently alive to the imminence of the dangers which frequently assail men whose livelihood is gained in the pursuit of coal, to induce them promptly, though cautiously, to make for the shaft. As they proceeded they several times became aware of something in the air, which tended to produce a drowsy sensation and this was enough to create an alarm of a lively nature. Though advancing in a careful manner which, to experienced miners, seemed prudent, they were not long in arriving at the shaft. The obstructions there, however, prevented their escape from the mine at that point and some of them, remembering that there was a staple communicating with the bottom of the back shaft, they directed their footsteps in that direction. Arrived at the foot of the back shaft, after creeping laboriously through the debris, their troubles were not yet ended, for some time elapsed before they could be brought to bank. They suffered extremely from cold and were certainly to be congratulated when at last they were relieved from terrible suspense and placed in a position where they could have warmth imparted to their shivering bodies. The process of hauling them up, however, was a slow and tedious one and was scarcely concluded before eight or nine o’clock in the morning.

In the meantime, the exploring party, under Messrs Morland and Lindsay, the first to descend and commence the gallant and beneficent work of rescue, having sent the men and boys already referred to up the shaft, pursued their investigations further. Most unhappily, however, they got separated, Mr Lindsay with Elijah Donnelly and Richard Coldwell (more commonly known as Slee), overmen, going up the ‘return’ while the others went up the ‘intake’. Whether the former bent their steps along the ‘return’ purposely or by mistake is unknown, but considering the extreme danger of such a course, it is probable that their taking that direction was an accident. They had not proceeded far before Donnelly manifested signs of weakness, the result of choke-damp, or as it is more generally termed, after-damp. Mr Lindsay and Mr Coldwell supported him for some distance and then Coldwell also began to show signs of failing. In this juncture it fell to Mr Lindsay to assist both. Mr Lindsay happily availed himself of his scientific knowledge to aid him in upholding himself against the effects of the impure air. As he went along he put nails in his mouth and sucked them and licked the rods. The result of this was that the carbonic acid, of which after-damp is composed, coming into contact with oxide of iron, carbonate of iron, which is an insoluble compound, was formed. Thus, though exposed to the after-damp as much as the others he did not absorb so much and therefore retained his strength much longer. He dragged his companions along with all the power he possessed, though they soon collapsed. In a few minutes, however, despite the precautions he had taken, he himself found his strength deserting him. He still clung to his ill-fated companions and altogether dragged them about ten yards when he was obliged to relinquish his grasp of them. By this time he was only half-conscious. Already, the deadly choke-damp had taken seriously hold of his faculties. Reeling in his endeavours to resist the fatal inducement to sleep he struggled forward in the (for a time) vain search for the other detachment of the exploring party. For three quarters of an hour he is said to have maintained the desperate struggle for life, being too far gone to think coherently or notice sufficiently his bearings to enable him to understand the best course to take and he would undoubtedly have suffered death in return for the heroic manner in which he had stood by his overmen if it had not been that his absence having been missed by the band of men with Mr Morland, Messrs Hulton and Hedley started out to find him, with ultimate success. They were, however, just in time. When they first came upon him he was sinking fast and by the time they got him to the bottom of the shaft he was in a state of complete collapse. This would be about half past one o’clock. News was sent to the surface of his critical condition and Mr Palmer asked Dr Wilson if he would consent to descend the shaft and examine him. On occasions such as these high courage seems to be the rule amongst all classes of men called together or to alleviate the sufferings of their fellows and the plucky little doctor promptly answered the eager question with, ‘Certainly, I will go.’ Dr Wilson replaced his coat and hat with the coat and cap and other accessories of a workman, entered a kibble, which was also occupied by the shaftsman, and was set down. By this time the two overmen were also brought to the shaft. These he found quite dead. Mr Lindsay was in a comatose condition. What could be done to restore him was done by Mr Wilson, after which he was sent up to the surface. He was then removed to his home, hard by, and continued medical assistance relieved him considerably, though he still suffers from severe shock to the nervous system. Mr Lindsay, describing the fearful time he had had, declared that many times he felt as if he must give up, but he succeeded in struggling on in the vague hope that he might yet be able to find some safe place. Coldwell was next placed in the kibble, drawn up to bank, and conveyed home. His death appeared to be caused by asphyxia. He had sustained no wounds and his countenance bore a remarkably placid expression. The next to ride was the body of Donnelly, whose death, as may be gathered from the foregoing, was caused by suffocation by after-damp. He had several bruises, which were supposed to have been occasioned by Mr Lindsay’s endeavours to save him.

Page 4

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

Pit Terms

Staple (or Stenton) - a short tunnel connecting two main roadways. A Staple is usually vertical and a Stenton horizontal.

Return - a roadway carrying used air out of the mine. Any afterdamp would leave the mine via return roadways!

Intake - a roadway carrying fresh air from the surface to the working areas of the mine.

Shaftman - a craftsman who specializes in shaft maintenance and shaft related procedures.

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

The other contingent continued their labours along the intake, their progress being slow out of regard to their personal safety and the obstacles they met with. From time to time they were recruited by further bands of volunteers, while others, exhausted with the labour, the cold and the damp, returned to breathe and regain their energies above ground. About half past four o’clock in the morning Mr J Forman, president of the Durham Miners’ Association, and Mr W H Patterson, financial secretary of that organisation, arrived. The latter immediately went down the mine to assist the rescuing party in their devoted work. He remained at the ‘face’ for nearly nine hours without once ascending, and then at last returning in a very weary state to bank to be indulged in a bath, changed his clothes and partook of much-needed refreshment. Mr Forman, who in the Seaham explosion very nearly lost his life and who indeed probably would have done but for Mr Lindsay, equally anxious to assist in the labour of the day, remained in the office and superintended the organisation of relays. The fact that Mr Lindsay, who so nearly perished, probably saved Mr Forman’s life at the Seaham explosion, will increase the interest felt on his behalf, and the hearty desire of all that he may be completely recovered more quickly than was Mr Forman, whose condition was so serious that his illness extended over three weeks. As the hours wore on the atmosphere at the mine became sweeter and purer and it was with intense gratification that the anxious watchers above learned from wearied workers from the depths of the mine that there was now a ‘good supply of air’ to be had below and that there was no longer any danger from impure atmosphere. The first perfectly organised shift of explorers who descended were in charge of Mr May, with Mr Parrington as his lieutenant. Later, another shift descended under Mr Morland, Throughout the day the men worked strenuously at a block discovered less than 300 yards beyond the shaft. This block was caused by a very excessive fall about 20 feet high, and as far as could be ascertained, about 30 feet thick. Their progress, however, was very much impeded by the fact that, as they endeavoured to cut a way through, the superincumbent debris kept falling in the spaces as they cleared them. Though necessarily slow, tedious and disappointing, owing to this cause, it was continued with spirit and, comparatively speaking, considerable headway was made by about six o’clock on Tuesday night, though, as the entombed men are said to be about a mile or a mile and a half further away, no hopes of their immediate recovery could be held out, as it was by no means unlikely that further blocks would have to be contended with. This accident is described as being, on a smaller scale, very similar to that at Seaham and this was regarded as confirmation of the doubts entertained as to the speedy recovery of bodies of the men beyond the falls. These twenty six men, it may be interesting to note, comprise J Lackenby, whose last descent of the pit was the first after his marriage, which took place a few days previously. Amongst those assisting in the operations in addition to those already mentioned were Mr F Stobbart, Lambton Collieries; Mr Willis and Mr T Bell, Government Inspectors; Mr R Foster, Gateshead, Mr W Parrington, Monkwearmouth; Mr Hedley, Wardley; Mr Berkely, Marley Hill; Mr WE Foggin, Biddick; Mr J Lyall, Washington; Mr Robson, Redheugh; Mr SC Crone, Killingworth; Mr VW Corbett, head viewer, Londonderry Collieries.

Page 5

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

LIST OF THE KILLED

A list of the men and boys killed in the pit has been compiled by Mr Leonard Hancock, the cashier at Usworth Colliery and, with the assistance of the secretary and agents of the Northumberland and Durham Miners’ Permanent Relief Fund, the number of widows and young children bereaved has been added to the list. The total number killed is 41, and this number includes the two rescuers who died from ‘after-damp’.

SHIFTERS

1. Thomas Crake (master shifter) leaves a widow

2. Moses Harlow, widow and four children

3. Michael Quin, widow

4. Henry Hunter, widow

5. David Beveridge, widow and two children

6. James Dawson, widow

7. John Ball, widow

8. James Clark, unmarried

9. John Tummelty, widow

10. John McGreve, unmarried

11. William Sparks, widow

12. William McLauchlan, widow

13. Robert Richardson, widow and five children

14. Robert Harrison, widow

15. John Ingleby, widow and one child

16. Samuel Brown, widow

17. William Brown, unmarried

18. Jonas Howarth, unmarried

19. John Outhwaite

HEWERS

20. James Cook, widow and four children

21. Martin Wallace, widow

22. Thomas Connell, widow and one child

23. John Wood, widow and one child

DEPUTIES

24. Matthew Winship, widow

25. Peter McQuillan, widow

26. Joseph Greener, widow and three children

27. William Carr, widow and six children

WAGGONWAY MEN

28. Ridley Taylor, widow and six children

29. James Walmsley, widow and one child

30. J Lackenby or Wetherell, widow

PUTTERS

31. John Taylor, unmarried

32. Thomas Kelly, unmarried

DRIVERS

33. Henry Murray (boy)

34. Thomas Murray (boy)

35. J Dinning (boy)

HORSEKEEPER

36. R Sylands, widow and three children

FIREMAN

37. William Howarth, unmarried

OVERMEN

38. Elijah Donnelly, widow and three children

39. Richard Slee, or Coldwell, widow and one child

CHOCK-DRAWERS

40. Charles O’Neill, the elder

41. Charles O’Neill, the younger

BODIES RECOVERED

The bringing of bodies to bank was necessarily proceeded with very slowly, and up to six o’clock on Tuesday evening only four bodies had been brought to bank, including Donnelly and Slee, two of the exploring party, who succumbed to the effects of the after-damp, and Taylor and Howarth, who were found near the foot of the shaft seriously injured by the force of the explosion.

Ridley Taylor, waggonwayman, Waterloo, about 37 years of age.

Elijah Donnelly, overman, Coxon’s Row, about 35 years of age.

Richard Slee or Coldwell, overman, Railway Terrace, about 40 years of age.

Wm Howarth, fireman, Railway Terrace, about 21 years of age.

LIST OF INJURED

Among those injured by the explosion of afterwards met with injuries during the exploring operations were:-

Thomas Dobson, boy, injured by force of explosion

Henry Robinson, foot slightly bruised by fall of stone

---- Prest, severe bruises of muscles of back

---- Buckham, scalds and burns, scalp wounds

Peter Quin, scalded about face

CS Lindsay, severe shock to system and effects of after-damp.

Page 6

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

LATER PARTICULARS

WEDNESDAY EVENING

It is now made clear that 41 men and boys were lost. In addition to the men there were seventy two horses in the pit and these, also, must have been killed. The work of exploration is difficult and trying and at every step fresh evidence of the force of the blast is apparent. Up to midnight on Tuesday the explorers had only been able to penetrate a distance of about 400 yards from the shaft. What is known as a ‘hitch’ had to be passed and here the roadway was blocked from floor to roof. The material to be moved was so soft and wet that as it was removed fresh falls took place. For a considerable period only one man could work at the face of the debris, his companions meanwhile removing the material which he pushed towards them. In order to make some more progress it was determined to prop up the roof and sides by means of boards. At half past one this morning some of the members of the shift that went down to work at six o’clock on Tuesday evening came to the pit head. In that interval the shift had only advanced a distance of four feet. More progress was afterwards made and about five o’clock this morning, after thirty hours of hard work, the explorers succeeded in getting through this heavy fall and they were soon able to penetrate 200 yards beyond that point. Here they found the way ‘upstanding’ though the doors etc had been blown out. The doors were restored to improve the ventilation, which, it may be mentioned, is effected by means of a large Guibal fan, of 45 ft blades. At eight o’clock a way had been cleared to a point 400 yards beyond the fall and at a place called the ‘Way Ends’, the first body was found. It was identified as that of Peter McQuillan, a deputy. He was sitting at his ‘kist’ with his body thrown forward, as if he had been awaiting the arrival of the men on the night shift, so that he might examine their lamps. The body presented a shocking spectacle. The head was bruised and the legs, arms and nose were broken. Great difficulty was experienced in moving the body to the shaft, the passage cleared being very rough and narrow. The body was brought to bank about ten o’clock, when it was reported that two other bodies had been found. These were supposed to be the bodies of the two waggonwaymen, named Lackenby and Walmsley; but it was impossible at that time to remove them. At noon the explorers had penetrated about 800 yards from the shaft but they expected to have to go nearly a mile further before they would find greater numbers of bodies. An hour later they had advanced another 200 yards, when progress was stopped by another heavy fall, which completely blocked the road; but operations were at once commenced to clear a way through the obstruction.

The entrance to the mine by means of the downcast shaft was both slow and dangerous and efforts were made during Tuesday afternoon and night to open out the main shaft, the bratticing of which had been shattered by the explosion, and access to the pit by this means stopped. The task was of a very laborious nature, but steady progress was made. At midnight 35 fathoms remained to be cleared before the bottom of the shaft could be reached. At half past four in the morning the shaft had been cleared for a distance of 15 additional fathoms; but as the workings were approached the destruction was found to be very great and considerable labour was necessary before the cage could be lowered to the bottom.

As to the cause of the explosion, that at present remains a mystery and it is doubtful if the problem will ever be solved. It was at first said that no shots were appointed to be fired on Monday in the pit, but it has since been stated that for the first time a shot was to be fired in a new drift, which is close to the face of the coal. Supposing this shot was fired, the accident would be easily explained; but as no one in the mine at the time can have survived to tell the tale, the only means of ascertaining the fact will be by a minute examination of the spot when it is reached and it is probable that the explosion of the gas may have made it difficult, if not impossible, to decide whether a shot was fired.

Page 7

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

Pit Terms

Doors - ventilation doors used to control air flow.

Kist - a Deputy's underground 'office' where he instructs his men about the day's work.

Downcast Shaft - the 'Intake' shaft where fresh air enters the mine.

Shot - the firing of a small piece of explosive, by a shotfirer, to assist the removal of naturally situated stone (or coal).

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

THE INQUEST

The inquest on the bodies recovered was opened this morning in the Infant School, Usworth, by Mr Coroner Graham, before a jury of seventeen of which Mr Thomas Wilson is foreman. Mr Willis, Government Inspector of Mines and Mr Forman, the president of the Miners’ Association, were present.

The Coroner, in the first instance, said that it would be apparent to the jury that it would be necessary the inquiry that day should be merely formal. The object of opening the inquest that day was to give the friends of the deceased opportunity to inter the bodies; and as further dead bodies were recovered it would be necessary that they should meet from time to time to hear similar formal evidence in respect to them. But in order that they might have all the facts before them, they must fix a day, sufficiently far distant to make the object practicable, when they could meet and thoroughly sift at the whole of the circumstances in connection with the terrible catastrophe that had happened; and when they did meet for that purpose they would sit from day to day until the inquiry was completed. He had been for taking counsel with Mr Willis, the Government Inspector of Mines, and he thought it would be well to have the ultimate adjournment as early as possible after Easter; say the Wednesday in Easter week (April 8th) when they would have got over the Easter holidays.

The Chairman of the jury asked if they had not better postpone fixing the day until things were riper for proceeding with the inquiry.

The Coroner said that it was necessary to formally fix a time. The Home Secretary might think proper to send someone down to attend the inquiry and, in that event, he would like to be informed when the inquiry would be resumed, so that the requisite arrangement might be made. After some discussion it was agreed to fix the 14th April at ten o’clock for the commencement of the thorough inquiry into the circumstances of the accident.

Charles McQuillan was then called and identified Peter McQuillan, his brother, who was a deputy-overman and 47 years of age.

Thomas Smith identified Richard Coldwell, or Slee, as his brother-in-law and said that he was a master-shifter and 43 years of age.

Edwin Donnelly identified Elijah Donnelly, his brother, who was a back overman and 44 years of age.

William Robson identified Ridley Taylor, his cousin, who was an engineman and 38 years of age.

John Howarth identified William Howarth, his brother, who was a fireman and was 20 years of age.

This concluded proceedings.

Page 8

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

RELIEF OF THE BEREAVED

All the men and boys employed at Usworth Colliery have been members of the Northumberland and Durham Miners’ Permanent Relief Fund for many years and J Bowes Esq and Partners, the owners, have contributed a percentage upon their workmen’s subscriptions. The number of members at Usworth is between 700 and 800 and their contributions last year to £580. Information of the explosion was sent to Mr Blyth, secretary, who forthwith went to Usworth, accompanied by Messrs W Steele and Jos Moses, agent, and Mr B Lowes, clerk, and were met there by Mr Geo Parkinson, Sherburn, the Chairman of the Executive Committee. With the aid of Mr Leonard Hancock, the cashier at the colliery office, a list of the men and boys in the pit was compiled and inquiries were made.

The amount which will be paid from the Fund under the head of legacies will be as follows: - 27 widows at £5 each - £135; 8 unmarried full members at £23 each - £184; and three half members at £12 each - £36; making a total of £355. A weekly grant of 5s will be made to each widow, and of 2s per week for each girl under 14 years and boy under 12 years of age. The total amount of liability entailed upon the fund by the explosion is estimated at about £6,000.

Page 9

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Article from Durham Chronicle

THE USWORTH EXPLOSION

Following up the narrative of this disaster the state of things at the pit yesterday (Thursday) was not greatly changed. About half past nine in the morning one side of the West Pit shaft was completely cleared. Gangs of men have been continuously employed since the accident happened in trying to clear this shaft, in order that communication might be opened out between it and the East Pit shaft, which are close together. Now that it has been cleared, a considerable number can go down it in the cage in a very short time, and by going through the brattice work which divides them at the bottom, get into the East Pit shaft and join the exploring party. The exploring party which went down at five o’clock in the morning was under the direction of Mr Hull, surveyor of the colliery, Mr Curry, surveyor at Hamsteels and other officials. At half past eleven o’clock, the party were relieved by another gang of about twenty men under Messrs Stokoe, Harris, Chicken and Scott. The reports brought to bank in the course of the morning were that the exploring party had reached what is known as the middle staith, and that what interfered with their work was the after-damp. Early in the morning several men had been more or less affected by it and they were therefore proceeding very carefully. As they progressed they shut off the after-damp with the brattice work, forced it round the ‘return’ and introduced fresh air. By this means they made slow progress and bent their energies towards the far face of coal where the bulk of men are entombed. The five o’clock exploring party came to bank about half past twelve o’clock and they reported that they had not made any progress since the last shift, they only having been engaged in securing and propping up the passage already made by the previous party. Operations were being carried on in the Middle North landing and they stated this was the part where the bodies of the two boys had been found. The air was bad, and it had not been deemed advisable to remove them. About one o’clock four of the exploring party were brought to bank suffering from the effects of the after-damp. Their names were John Robinson, John Burrell, Marshall Davey and Mr Morland, son of the resident viewer. Restoratives were applied by Drs Jackson, Wilson and Nance and the men, who were not very badly affected, were soon able to proceed home. Davey was the worst. They had been struck by after-damp while putting up bratticing to shut it off. The excitement in the village had abated to a very considerable extent and only about a score of persons were gathered round the pit barricading.

Page 10

The above paragraph appeared on Page 3 of the newspaper. The main article started on Page 7.

[ Transcript prepared and contributed by Peter Welsh, Coordinator of Wessington U3A War Memorials Group ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

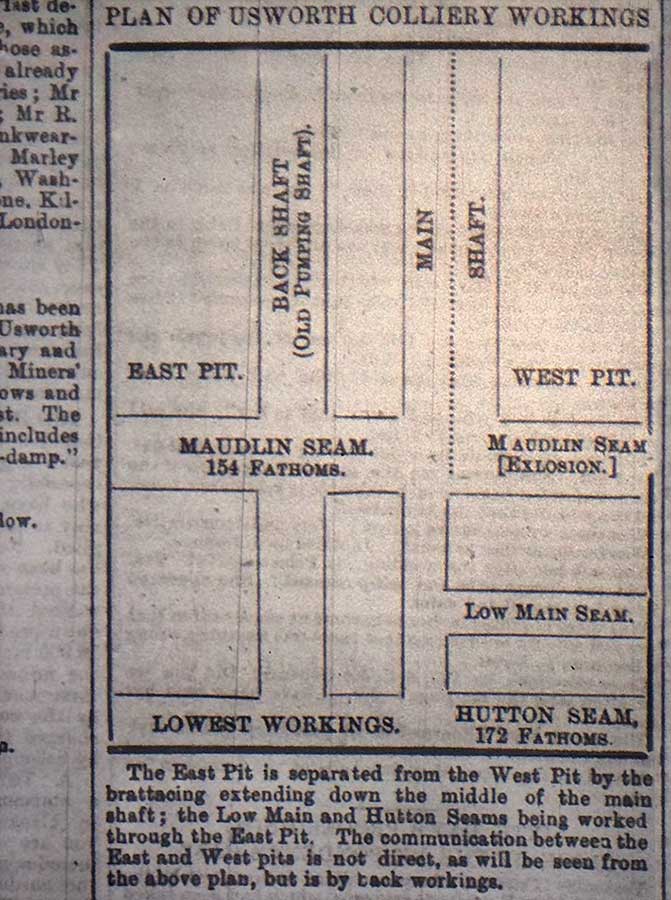

Map from Durham Chronicle

This Map accompanied the Durham Chronicle Article.

[ A Fathom is a unit of length / depth, equal to 6 feet. ]

USWORTH COLLIERY DISASTER

( Monday, 2nd March 1885 at 8.58 p.m. )

Overman Donnelly's Bravery Remembered

Elijah Donnelly's Commemorative Jug

Inscribed to record Mr Donnelly's selfless act of bravery in entering the disaster area

with two colleagues to attempt a rescue. This Glass Jug stands 7 cm tall and reads:

In Remembrance of Elijah Donnelly.

The Beloved Husband of Jane Donnelly.

Who Perished in an attempt to Rescue

his fellow workmen at

Usworth Colliery Explosion March 2nd 1885.

Aged 44 years.

[ Thanks to Mr Donnelly's great-granddaughter, Marian Morgan, and her cousin, Tom Hunter. ]

• • ◊ • •

This Tragic Story continues on Page 2/2 with Peter's transcripts of The Adjourned Inquest. See Top Menu.